Romanticism, musicals, and pop culture in the construction of a dangerous emotional myth.

Every February 14th, we don’t just exchange flowers or promises; we also unconsciously renew a very specific emotional pedagogy.

Valentine’s Day exists, in part, to remind us not only how love is supposed to feel but also how to recognize it. Within this social framework, certain patterns are legitimized as desirable in the romantic realm: intensity, exclusivity, devotion. Love is measured by sacrifice and celebrated the more it exceeds the bounds of reason.

The romantic narratives we uphold culturally are far from innocent. They have trained us to confuse insistence with devotion, dependence with emotional depth, and suffering with authenticity. Beneath the guise of passion, certain behaviors cease to alarm us and come to be read as inevitable—even desirable. Perhaps that is why some stories do not disturb us as they should: we do not view them from the lens of horror but from that of romantic empathy.

Romanticism and the Legitimization of Emotional Excess

These perceptions of love, which we now recognize as problematic, are deeply linked to the conceptual and aesthetic pillars of 19th-century literary Romanticism. In this framework, the only legitimate love is intense, obsessive, and sacrificial—a tidal wave of emotion that carries profound suffering, where pain and attachment stop being symptoms and become intrinsic virtues of the romantic bond.

Romanticism focuses on the isolated subject: the misunderstood genius whose emotional excesses are justified by the very existence of his suffering. In parallel, the figure of the beloved is constructed as a muse and a promise of salvation. Her narrative value does not lie in who she is, but in how much she can repair, redeem, or contain the wounded subject.

From this logic, ideals of relationships defined by codependence, control, and the dissolution of individuality in favor of a collective “we” are reinforced. A “we” that is not truly mutual, because it arises not from recognition but from sacrifice: the forced cultivation of shared emotional territory and the creation of a hybrid identity in which singularities are subordinated to the symbiosis.

It is no coincidence that one of the foundational myths of this imagination continues to return with force. Wuthering Heights, published in 1847, now re-enters the cultural conversation with a new film adaptation directed by Emerald Fennell, released just before Valentine’s Day. Heathcliff and Catherine have been read for generations as tragic lovers, when in reality they precisely embody a relationship based on possession, emotional dependency, and revenge as a playground. Their story is not a celebration of romantic love but a cautionary tale we have learned to consume as fantasy.

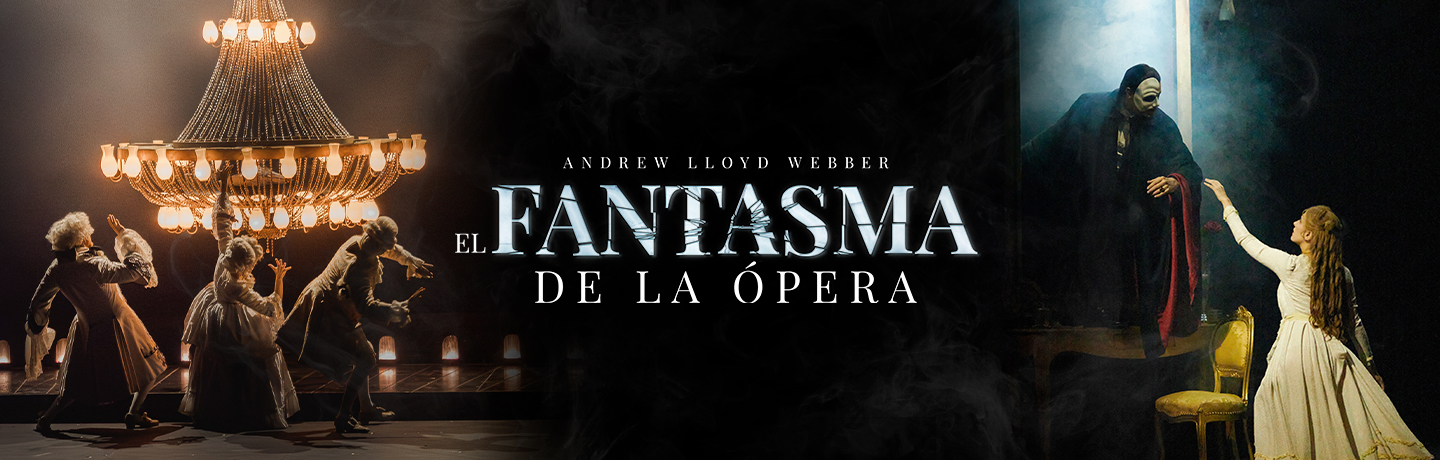

The Phantom of the Opera: The Last Romantic Work

To what extent can the idealization of certain attitudes in human relationships become dangerous? How hard is it to dismantle myths that hover in the ambiguous space between prince charming and the solitary lover, between absolute devotion and romantic isolation? And what happens when our cultural imagination has taught us to distrust love that does not promise extreme sacrifice—even when that sacrifice approaches, or crosses, the line into emotional violence?

In this sense, The Phantom of the Opera can be read as one of the last great inheritances of Romanticism. Not so much for its Gothic aesthetics or its exaltation of passion, but for the affective logic that sustains its protagonist: the wounded subject who turns isolation into identity and desire into entitlement.

If we attempt an aesthetic deconstruction and analyze the Phantom stripped of his music, his cloak, and his mask, the question is inevitable: would we still overlook his actions, or would we recover the natural rejection they should provoke? What remains is not a tragic lover but a man obsessed with a young woman he tries to bind to him through emotional manipulation: presenting himself as the voice of her deceased father, using music as a tool of dependency, and forcing an intimacy that was never consensual.

His behavior quickly escalates into control and coercion. He watches her from the shadows, intrudes into her private space, abducts and isolates her, questions her ties to the person she truly loves, and dismisses any refusal as a narrative obstacle rather than an expression of will. When Christine resists, the response is not withdrawal; instead, the escalation occurs: threats, symbolic punishments, and the imposition of marriage as the only possible solution.

The Musical as a Device of Emotional Whitewashing

The format in which a story is told, while not altering the fundamental facts of the narrative, can radically transform its reception. At the level of script and musical language, The Phantom of the Opera shifts the emotional focus from the character’s actions to his suffering, inviting the audience to read the violence as a consequence of pain rather than a choice. The result is a perceptual inversion: what should provoke alarm is presented as intimate tragedy.

Dramaturgically, the Phantom occupies the emotional center of the conflict. His musical numbers articulate his inner story, giving him psychological depth, while Christine is often relegated to the role of catalyst for that pain. Music establishes a hierarchy: the one who sings his wounds is the one who deserves understanding. The script builds structural empathy with the aggressor—not because it hides his acts, but because it wraps them in a logic of emotional justification.

Musically, this operation becomes even more effective. The melodies associated with the Phantom—broad, enveloping, and highly lyrical—activate an immediate emotional response that neutralizes the audience’s critical judgment. Vocal beauty and orchestral intensity act as a substitute for narrative ethics: we feel before we think. When the character sings his loneliness, desire, or pain, the music softens the content of his actions and reframes it as an expression of extreme love, rather than a manifestation of control.

In this way, the musical masterfully achieves the aestheticization of horror. And in doing so, it transforms the audience’s experience: we no longer witness a story that should disturb us, but a romantic tragedy that invites compassion.

The Power of “How”: Melody, Tone, and Emotional Manipulation

Melody, tone, and vocal cadence can turn simple words into instruments of persuasion, fascination, or coercion. In The Phantom of the Opera, this is evident in numbers like Music of the Night or the iconic duet The Phantom of the Opera. Music does more than accompany the action; it guides the audience’s perception, making a message of control, obsession, and threat read as seduction and shared vulnerability.

Consider The Phantom of the Opera: the lyrics speak of power and influence—“Our strange duet / My power over you grows stronger yet”—but it is the combination with tense harmonies and dramatic crescendos that transforms this statement into an act of aesthetic fascination. Christine sings and resists, but the music grants the Phantom an irresistible aura: the how of expression outweighs the what. Threat, isolation, and invasion of personal space are reinterpreted by the audience as intense intimacy.

A modern parallel can be drawn with Every Breath You Take by The Police. The lyrics—“Every breath you take, every move you make, I’ll be watching you”—could be read as obsessive control and constant surveillance. Yet the soft melody, slow rhythm, and melancholic tone culturally recast it as a gesture of romance. What Sting wrote as obsession becomes, in the listener’s experience, legitimate affection.

In both the musical and the pop song, the effect is the same: the how transforms the reception of the message. Melody, harmony, rhythm, and tone reshape the audience’s moral and emotional judgment, allowing behaviors that should trigger alarm to be experienced as beauty or legitimate emotion.

It is imperative that, as an audience, we learn to activate critical distance and view these stories through the proper lens. Music, tone, and staging carry enormous emotional power: they can beautify violence and romanticize control. Recognizing this mechanism does not mean renouncing aesthetic pleasure or denying the artistic value of the work; it means embracing it with greater maturity. We can admire the musical and narrative complexity of The Phantom of the Opera—its formal sophistication, its seductive power—without endorsing the behaviors it portrays. Enjoying a story does not require morally absolving its characters, and understanding how art manipulates our empathy is, now more than ever, a form of cultural responsibility.

By the LETSGO Pen, Claudia Pérez Carbonell, on February 12th, 2026