From Munch to Burton, a journey through the beauty of the macabre and its transformation into a global icon of consumption.

Every autumn, Western culture and ritual turn their gaze toward the dead. Across much of the Catholic world, All Saints’ Day preserves a solemn tone of prayer and contemplation; in Mexico, however, the Day of the Dead transforms remembrance into a colorful and symbolic celebration. Rather than praying for the departed, people share space with them: altars are built, their favorite food is offered, and their memory is celebrated as an annual visit that brings the absent back to life.

Meanwhile, in the Anglo-Saxon world, Halloween reshapes the same relationship with death into a playful spectacle of consumption —costumes, masks, orange lights, and a domesticated kind of fear. Through globalization, this festive and commercial version has extended far beyond its original borders, resonating in cities across the globe. Two traditions, distinct yet converging in their essence: both seek reconciliation with the idea of death, whether through devotion or play.

The limbo that emerges between these perspectives has always been fertile ground for creativity. The most twisted and visionary — even marginalized — minds find inspiration in that in-between space and the ethereal themes surrounding it. Tim Burton stands among the most emblematic cases: his cinema makes darkness a place to dwell in. He has crafted an aesthetic that brings the gothic and the strange closer to audiences of all kinds. In his universe, death is no longer taboo, and his characters embody the perfect symbiosis between the macabre and the endearing.

The Burtonian Universe: Physical Deformity as an Extension of the Inner Self

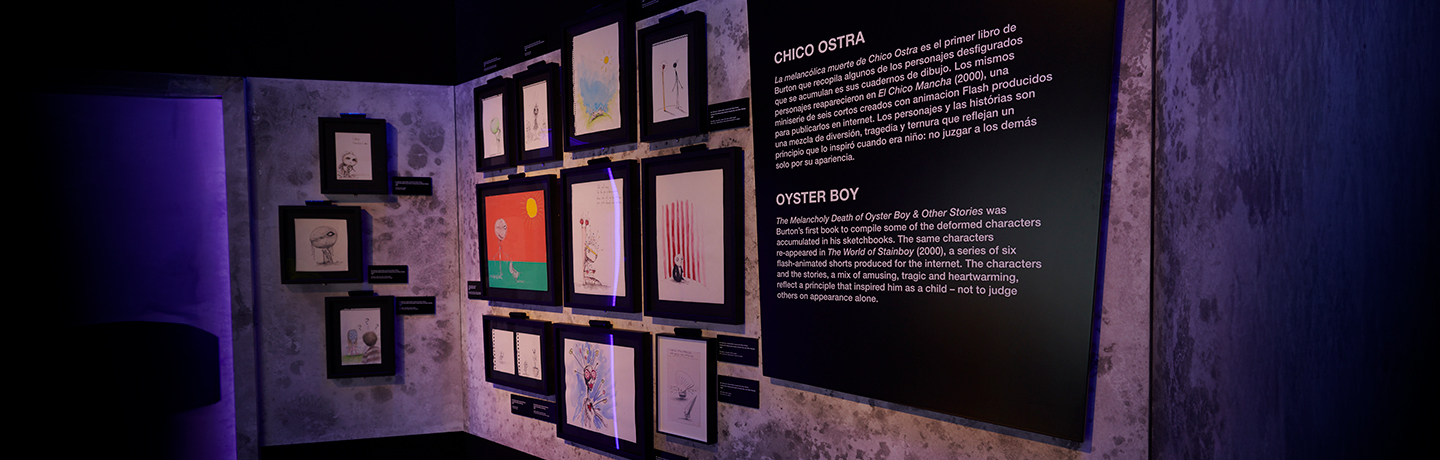

The funerary imagery that populates Burton’s worlds is instantly recognizable: melancholy, gothic elegance, and the beauty of the odd and the deformed. His characters are equally profound in alienation, solitude, and emotional complexity.

Burton builds his visual poetics through precise detail. His protagonists often have exaggeratedly large eyes or sharply defined facial cavities, amplifying vulnerability and emotional intensity. His color palette often revolves around blacks, greys, and blues, reinforcing a sense of strangeness and melancholy. A clear example appears in Corpse Bride: the world of the living is rendered in near black and white, austere and rigid, while the world of the dead bursts into color, transforming death into something festive and close.

His settings share in this poetics —tilted houses, twisted trees, tortuous streets— all functioning as extensions of his characters’ psyches. What emerges is a language of the grotesque and the macabre, organically woven into his visual narrative.

This deliberate distortion of bodies and spaces establishes a clear parallel with German Expressionism and iconic works such as Munch’s The Scream: twisted geometry, disproportionate faces, anguished figures — all meant to convey emotion rather than depict reality. Like the expressionists, Burton uses exaggeration to communicate the inner world and, in doing so, grants darkness a new tenderness.

Contemporary Culture and the Dissolution of the Strange

We live in an age where the strange no longer feels strange. Globalization has blurred aesthetic and cultural boundaries to the point that the bizarre has become predictable. Horror, excess, or difference no longer unsettle —they are consumed with delight. The uncanny has lost its power to disturb, anesthetized by a society that has seen everything, that metabolizes even what once unsettled it.

Freud (1919) defined “the uncanny” as the return of the familiar from the repressed, what we recognize but refuse to face. In contemporary society, however, that return no longer produces shock. Discomfort has been replaced by style, and the abject —in Kristeva’s (1980) sense, as that which threatens identity or symbolic order— becomes an object of desire and consumption.

In this transition, “the strange” has undergone a paradoxical evolution: from marginalized to celebrated, and finally, to integrated. During the 1970s and 1980s, eccentricity operated as counterculture, a declaration of difference against the canon. Today, its presence barely causes dissonance. The gothic, the melancholic, and the eccentric have become catalog products. Phenomena such as Wednesday or the aesthetic revival of dark glamour confirm that what was once subversive is now decorative: otherness turned into trend.

One could say we have reached an age of extreme acceptance, where every form of difference is absorbed without resistance. But is that acceptance a sign of openness or exhaustion? Oversaturated by stimuli, wonder fades: no strangeness remains because everything can be assimilated by the machinery of taste and the market. In this “society of the spectacle,” as Debord (1967) foresaw, even the marginal becomes part of the circuit of consumption.

The greatest risk of this anesthesia of the strange may not be aesthetic, but cognitive. When everything can be integrated without friction, we lose something essential: the capacity to read the world with estrangement. The human gaze, once analytical and symbolic, able to interpret the signs of the unusual, now slides across the surface. What should provoke reflection becomes another recognizable pattern.

This loss of disturbance entails a loss of thought. Without wonder —that first moment of critical distance before what we don’t understand— judgment dulls, and imagination shrinks into mere consumption.

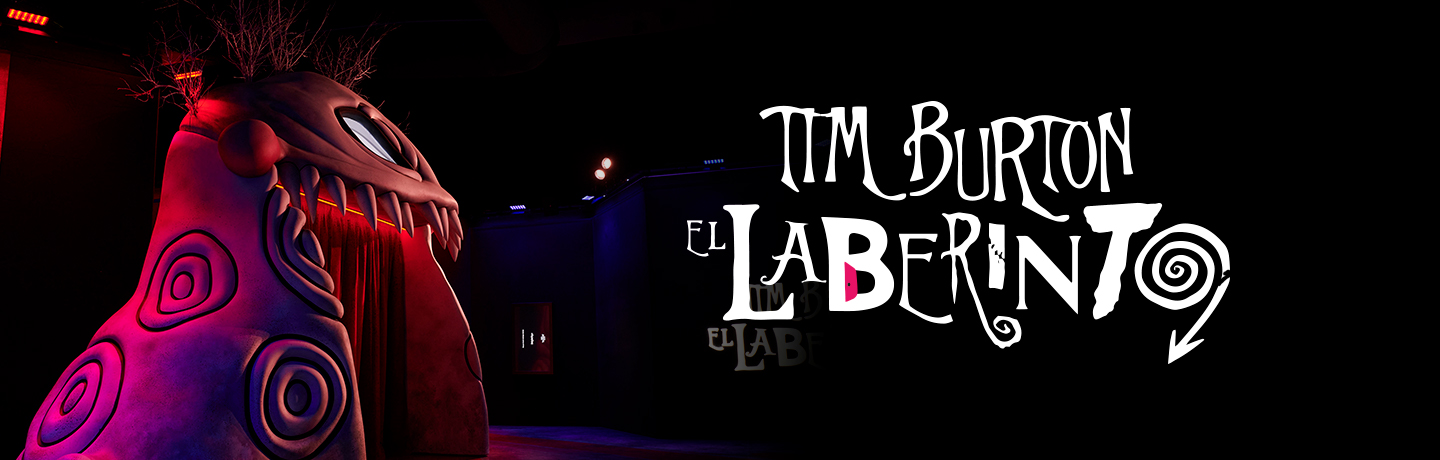

From Sketch to Experience. LETSGO and Tim Burton: The Labyrinth

Within this context of assimilation, Tim Burton: The Labyrinth, currently in Mexico City, emerges as an exercise in re-enchantment —an experience that restores the viewer’s ability to wander through the unusual from within. With this exhibition, LETSGO succeeds in translating Burton’s visual universe into an immersive format, treating space as an extension of the filmmaker’s imagination. Each room and corridor function as fragments of his mind, a journey that feels less like an itinerary than a walk through Burton’s own psyche.

The aesthetic lies not only in the decoration but in how visitors experience it: the contrasts of light and shadow, colors that embody emotion, sounds that are both unsettling and tender. Everything works together to immerse the spectator in a world where the macabre becomes intimate and the strange, familiar.

The fragmented route mirrors the logic of Burton’s films: there is no single path or rigid order. The visitor moves through spaces that overlap and contradict each other, like thoughts or memories colliding inside a creator’s mind. In this way, LETSGO transforms the experience into more than a visual homage —it recreates the sensation of inhabiting a universe where deformity and melancholy coexist with beauty.

Between Death and Fantasy: Burton Finds a Home in Mexico City

It is no coincidence that Tim Burton: The Labyrinth has found its home in Mexico City. The city shares with the director a unique sensibility toward the strange and the somber: its culture celebrates death with a color and intimacy that seem drawn from a gothic tale. Altars, skulls, and Day of the Dead rituals reflect a familiarity with the ethereal and the dark, turning local visitors into natural accomplices of Burton’s universe. This is not merely an exhibition —it is an encounter between Burton’s aesthetic and Mexico’s tradition of honoring death as part of life, where visitors feel immediately at home— a home that is nothing but a labyrinth of endearing deformities and emotions.

Beyond Fear: Inhabiting the Strange

Tim Burton: The Labyrinth is more than a visual homage; it invites us to rethink how we perceive what feels strange. In every room, deformity ceases to be an aesthetic flaw and becomes a collection of emotions, misunderstandings, and vulnerabilities. The viewer does not merely observe, they inhabit Burton’s world, entering a constant dialogue between melancholy, fantasy, and Mexico City’s own celebration of death. By the end of the journey, one leaves with the sensation of having traversed a labyrinth of ideas and feelings, where the somber becomes familiar, the bizarre becomes beautiful, and the experience redefines what we mean by “monster.”

By the LETSGO Pen, Claudia Pérez Carbonell, on November 5th, 2025