How contemporary are Harry Houdini’s demons? The new musical invites us to reflect on success, egocentrism, and emotional escapism.

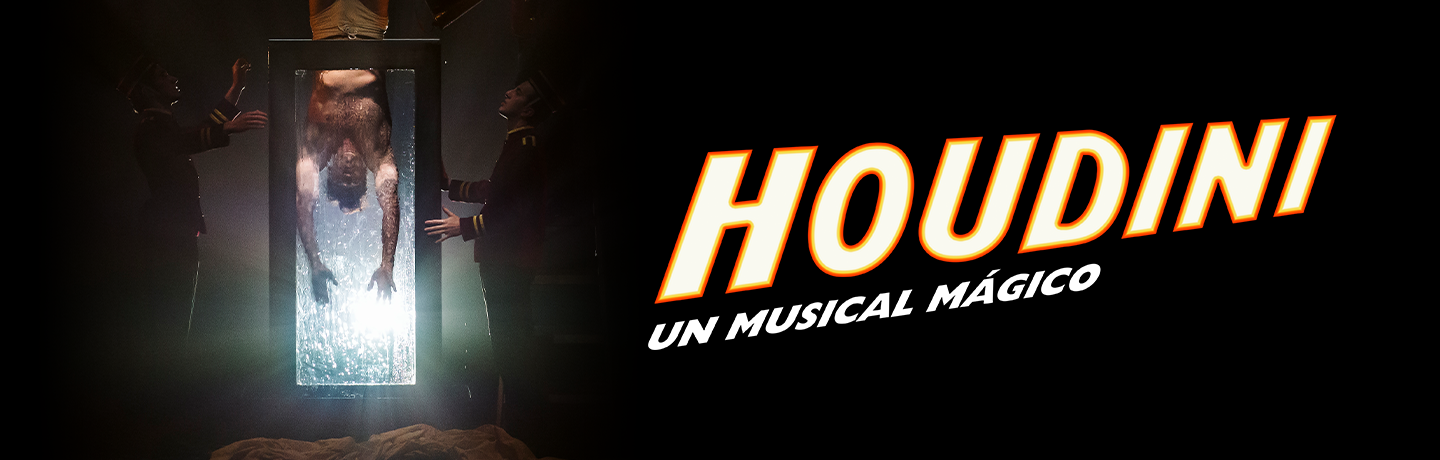

Harry Houdini was the man who took magic out of the streets and turned it into spectacle. The new production about his life unfolds mostly in an empty, ruined theater. Federico Bellone —the musical’s author and director— insists that this is not just an aesthetic choice: the decayed space serves as a metaphor for exhausted success, for a model of entertainment —vaudeville— that, by the 1920s, was already showing signs of decline. At the same time, Houdini’s own career was following the same downward curve. The set design, therefore, works as a statement: the musical does not aim to portray only the mythical escapist, but also the exhaustion of someone obsessed with being first.

Then, one of the central questions of his story arises —a question that still resonates today:

What do we mean by success? Does it really exist, or is it merely a construction tied to our contemporary craving for recognition?

Houdini: Anatomy of Modern Success

Alain de Botton (2004) argues that success is inevitably linked to status and comparison with others: it is never absolute, always relative. In this logic, Houdini already embodied psychosocial traits of our time. He suffered from an obsession with visibility and notoriety, from emotional detachment that made it difficult to sustain lasting relationships, and from an egocentrism that turned every poster with his name into an extension of himself.

That same obsession reverberates today in phenomena such as hyper-productivity, strongly tied to the pursuit of success, and the guilt associated with rest. Bellone acknowledges this bluntly:

Nowadays it happens often (…) successful people struggle internally to do the most incredible things. It’s as if not working for two minutes carries a sense of guilt that isn’t normal. Humans weren’t made to work all day and all night, but that’s what’s happening today, especially with social media, with the phone. The other day I was sitting in the sun for a while and thought, ‘oh, I’m not working, this isn’t right.

Byung-Chul Han (2010) expands on this in La sociedad del cansancio: the contemporary subject is not oppressed by an external master, but by themselves. The performance society turns external demands into self-imposed pressure, wrapped in the illusion of freedom. In this framework, rest feels like betrayal, and productivity becomes the only path to legitimacy.

This perspective allows us to read Houdini’s life differently. He was not only an extraordinary escapist, but also an extreme reflection of the modern obsession with performance and visibility. As Han suggests, contemporary success chains us more than it frees us, and de Botton reminds us it is always relative: never fully achieved, always measured against someone else. The media have changed, but the logic of obsession, self-exploitation, and visibility still grips us today.

Egocentrism Onstage and Offstage

Today, social media is the natural stage for contemporary egocentrism. A century earlier, Houdini had already mastered the logic: he turned his name into a brand long before Instagram existed. His face and his oversized letters flooded theaters and newspapers, reminding audiences that the real spectacle was himself. Onstage, the empty theater and the posters serve as symbols of that personality.

The difference lies in purpose. While the escapist exploited his image to sell tickets, today’s self-promotion pursues visibility as an end in itself. Personal validation is measured through the gaze of others. This logic had already been anticipated by Feuerbach in the 19th century, when he warned that modernity prefers appearance over reality, representation over being, until illusion becomes sacred and truth profane.

Emotional Escapism: The “Houdini Syndrome”

Some psychologists have drawn a striking parallel between the magician and our society. If Houdini escaped from chains, handcuffs, and water tanks under the fascinated gaze of the audience, today the most common escape happens quietly and offstage: fleeing from relationships, from discomfort, from confrontation.

In that sense, the so-called “Houdini Syndrome” works as a metaphor for contemporary emotional detachment: the tendency to disappear when a relationship becomes too serious or demanding.

The echo of today’s ghosting phenomenon is clear: evasion becomes a strategy to preserve one’s image, control, or illusion of freedom —even at the cost of breaking bonds abruptly. Disappearing without a trace is now a new form of power, tied to a longed-for aura of mystery.

This heritage of contradictions —success and decay, visibility and emptiness, escape and desire for permanence— also structures the new Houdini: A Magical Musical. Bellone and his team aim to humanize the myth, showing that behind the spectacle and the appearance of perfection lie universal tensions: ambition, fear, loneliness. That proximity will make audiences identify deeply and immediately with the magician’s dilemmas.

Houdini Through Light, Space, and Music

As already noted, the musical’s technical and scenographic elements support the psychological construction of Houdini. Lighting, designed by Valerio Tiberi, is another key resource in both the characterization of the protagonist and the audience’s perception of magic. Federico Bellone explains:

The lighting is very real. We want the audience to perceive a sense of strong verisimilitude, because magic in a real place has much greater impact. When there are many curtains or scenery that looks fake, it’s normal for the audience to think someone is hiding in every corner of the stage.

But when a character, or even an elephant (as we have in this show), appears in a completely empty theater, where you can see the walls of those American theaters with bricks and worn-out posters, the magic effect is much more impactful, because it’s impossible to imagine where it comes from. The lighting has a vintage feel, true to the American variety theater era, but it also conveys a strong sense of reality.

(…)

Houdini is different [compared to The Phantom of the Opera]: more emotional. Behind a gauze curtain you can discover much more human spaces. I don’t want to say it’s intellectual, but it is more personal.

The combination of light and space allows the audience to experience the tension between grandeur and vulnerability, between the need to shine and the solitude of the character.

Music, in turn, provides a counterpoint between spectacle and intimacy. Composed by Giovanni Maria Lori, it pays homage to Broadway theater while incorporating a Hungarian accent —Houdini was born in Budapest and emigrated to the United States at the age of four. The songs reflect the theater and dance of the era, with tap, Charleston, Can-Can, and, of course, the rhythmic turn of the Hungarian csárdás.

Bellone identifies the show’s soul in the song The Greatest Magic Man:

It blends Broadway and Hungarian csárdás. It describes how Houdini, even while feverish, was obsessed with work and with being first at everything —a central theme of the musical, he explains.

Throughout the production, there is a clear attempt to return to what is most human: a bare stage, real lighting, a Houdini stripped of his costume in much of the action, and a score that rescues his roots and elevates them to spectacle. All of this transforms the grandeur of the myth into a familiar, recognizable experience —closing the circle between spectacle and vulnerability that makes him so contemporary.

By the LETSGO Pen, Claudia Pérez Carbonell, on September 16th, 2025