A reflection on creativity, social pressure, and how advertising turns desire into a sign of belonging during the highest-consumption season of the year.

“Needs do not produce consumption; consumption is what produces needs.”

Jean Baudrillard

Communication as a Social Act

All communication is, first and foremost, a social act. When we communicate, we make a choice —consciously, in the best of cases— about what we express and how we express it. Even in its most basic form, communication requires a sender, a message, and a receiver. But as Jakobson (1960) noted, that triangle is not enough: we also need a shared code (language, gestures, references), a channel through which the message travels (voice, screen, chat), and a context that gives meaning to what is said —an already established cultural frame in which words and images take shape.

From this perspective, commercial communication can be understood as a sub-language that only works if it grasps the collective imagination in which it operates. It is not enough to want to say something; one must say it using the codes people already share. Advertising survives through a constant reading of the cultural climate, one that dictates what means what at any given moment.

This tension between language, culture, and strategy becomes especially clear in a reflection from Ana María Voicu, Creative Director at LETSGO, who captures the distance —but also the kinship— between art and commercial communication:

What is art, if not the need to give form to the invisible? An attempt to capture an emotion, a thought, a wound, or a hope and turn it into something visible, tangible, shareable. Art is, by nature, an individual act.

It is born in solitude, in an intimate place where no one else can enter.

Advertising, on the other hand, is born in company. It is collective, strategic, and coordinated. It needs a team, a structure, and pacing. It feeds on objectives, budgets, timelines, and audiences.

Her perspective illuminates the core of this discussion: if art is born inward, advertising is born outward. Yet both, ultimately, work with the same raw material: meaning.

Between Art and the Market: The Territory of Creativity

In the limbo of that tension, a question emerges —one that cuts through all creative work within the commercial system: who conditions whom?

Is creativity what opens the path, pushing brands toward new ways of saying, seducing, and signifying? Or is it sales —with their metrics, timings, and urgencies— that draw the boundaries of what is possible and force creativity to follow the rhythm set by the market?

Creating, in this context, is not so much an act of freedom as it is an act of reading the environment: reading the audience, reading the culture, reading expectations… and adapting.

And if there is ever a moment when this power dynamic becomes explicit, it is in the consumption calendar. Black Friday, Cyber Monday, and Christmas form the annual laboratory where creativity and advertising challenge and negotiate with each other to reach the same goal. On this, Voicu notes:

As a creative director, I work exactly on that border. Between the need to preserve the depth of art and the obligation to transform that emotion into something understandable, sellable, public.

My work is to build imaginaries that are at once beautiful, honest, and effective; that move and communicate. It is not only art: it is communication, message, narrative, audiovisual language. It is finding the aesthetic breathing behind a concept and translating it into an experience many can feel as their own.

Brands demand campaigns that are not only clever, but functional within an ecosystem of extreme saturation. This time of year is particularly revealing: the market sets the tempo, and creativity tries to carve out a space to stand out among the overcrowded gallery competing for our attention.

The Determinants of Creativity

It may seem paradoxical to question whether creativity has limits —or even to entertain the idea of imposing them. Yet today, what determines how creativity can —or cannot— unfold is the architecture of the media where it circulates.

Scrolling has become the new metronome of desire: a mechanical, almost unconscious gesture producing adrenaline spikes that determine what lives and what dies in seconds.

Immediacy is now the prerequisite of any creative gesture, and format —more than concept— dictates the aesthetic possibilities. In this digital ecosystem, creativity is born already conditioned by algorithms that seldom reward complexity or true artistry; instead, they favor what can be captured in an instant.

The Industry’s Snowball Effect

Historically, art has been the realm of the symbolic, the ambiguous, the ineffable. But the moment advertising began to draw from it —to gain aura, prestige, “sensitivity”— the reverse phenomenon was triggered: it was advertising, not art, that ended up dictating how the public looks and understands.

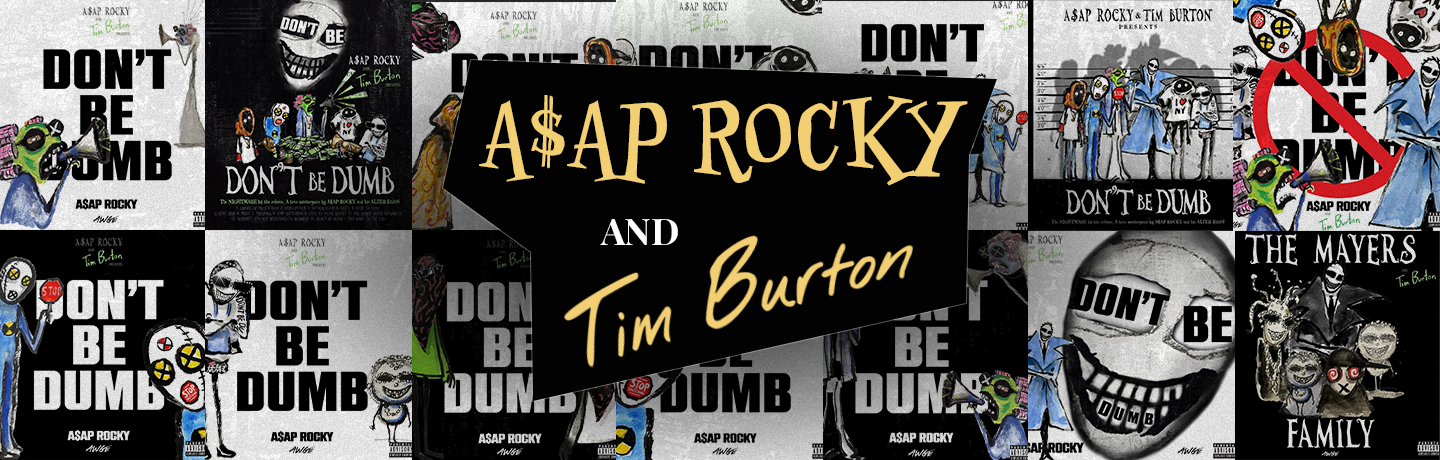

Today, brands appropriate cinematic codes and cultural references, crafting campaigns that boast “concept” in an effort to disguise the ultimate goal: selling.

The contemporary viewer, trained by decades of instant-impact imagery, no longer approaches a piece seeking depth but stimulation: empathetic colors, digestible compositions, emotions delivered through slogans. And thus the circle closes: an aesthetic born in art feeds consumption; mass consumption, in turn, demands repetition until that aesthetic is emptied out.

We find ourselves inside a formula that fuels the ever-spinning wheel of consumption —one that grows by accumulation, like a snowball.

Consuming to Belong: The Pressure of Visibility

It has been a long time since basic needs dictated human consumption. That pyramid has inverted: now it is consumption that generates new needs and establishes fictional hierarchies of priority. And it fulfills a fundamental social function: the desire for belonging.

We do not buy products; we buy symbols, signals of inclusion, shared cultural references. Every new trend or coveted object becomes a reminder of the social hierarchy within a group.

Buying is not just a right or an individual pleasure; it is a way of conforming to social expectations, of participating in a system where visibility and possession define our place. It is a form of pressure that shapes identities and worldviews. The obligation to consume in order to belong —and the resulting loss of freedom— has become one of the tacit rules of our society.

Influencers and the New Cartography of Desire

Where social pressure once operated silently, today it finds an almost infinite amplifier in new media and influencer culture. The multiplication of channels —TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, reels, stories— has transformed consumption into the centerpiece of content.

Hauls, product reviews, unboxings, recommendation lists, more than informing, they exist to generate further consumption, encouraging audiences to reproduce the same aspirations and desires.

In contrast to traditional brand-made content, influencer-generated content introduces new forms of advertising and creativity. Here, the creative margin not only exists but must align with the creator’s personality: their voice, style, and storytelling become the platform on which advertising is constructed.

Creativity becomes not just brand strategy, but a dialogue between product, creator, and audience —with the implicit goal of producing desire and consumption.

The effect is double: belonging to a group that knows, owns, and shares is reinforced; at the same time, pressure intensifies because everything becomes public and comparable. It’s no longer just about wanting something, it’s about wanting it where others can see, measure, and validate it.

FOMO and Contemporary Discrimination

If influencers amplify social pressure, FOMO makes it nearly tangible. What appears trivial —reduced to memes and catchphrases— is in fact a deeply class-based mechanism: not everyone has the same resources, time, or access, and that determines who participates and who is excluded from the collective narrative.

FOMO produces a double frustration: moral and economic. Frustration at not accessing the desirable, not forming part of the shared flow of trends, and frustration at the implicit obligation to compare oneself with those who can.

In this sense, FOMO becomes a social filter: it separates those who can keep up with performative consumption from those who, whether by choice or constraint, cannot. Those who do not consume fall out of the conversation —out of visibility—and are relegated to the margins.

The Aura of Stepping Outside the System

But not everyone is swept up by the wheel of consumption. Those who deviate —choosing second-hand clothing, vintage, upcycling, or living without social media— seem to acquire a mystical aura, or are labeled as “antisocial.” Their resistance does not free them from social judgment; instead, it becomes a source of fascination or categorization.

Being “alternative” becomes an identity in itself, and even the refusal to consume becomes commodified: independence, ethics, and conscious choice turn into brands of identity that others admire, imitate, or symbolically consume.

Even genuine resistance is thus absorbed into the system of visibility and value created by the consumer society. Choosing not to follow the current does not eliminate social pressure, it merely changes its form.

Consumption in the Guise of Art

The underlying question remains both ethical and aesthetic: what does it mean to create —and consume— within a society where everything becomes symbolic merchandise?

Can creativity preserve its freedom and depth when the market demands immediacy, visibility, and validation?

As Ana María Voicu reminds us:

Art and advertising are not enemies. They are two different forces that, when they engage respectfully, can generate something powerful: messages with soul, images with depth, experiences that sell… but also move.

To look, choose, and create consciously —in the sense John Berger (1972) advocated— seems to be the only way to recover meaning amid saturation, social pressure, and the constant noise of consumption. Because, in the end, both creativity and consumption are acts of interpretation, of relating to the world and to others.

By the LETSGO Pen, Claudia Pérez Carbonell, on November 27th, 2025