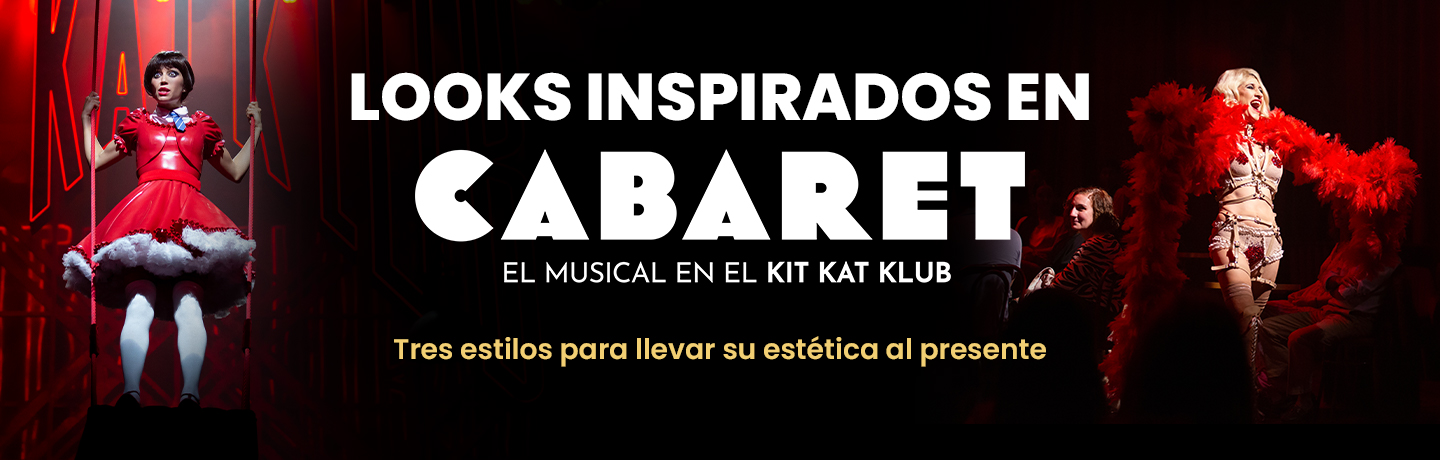

Based on an exclusive conversation with the set and costume designers, we explore how Cabaret has been updated without losing its essence, a work that continues to question history, gender, and freedom.

80 looks, 400 garments, leather, latex, rhinestones… is this what we picture when we think of a musical theatre classic?

The ensemble during the opening number, on a stage transformed into an immersive club setting.

Finding the balance between respecting a classic and reinterpreting it for new generations —so that it continues to speak to the times in which it is performed— can be challenging, even guilt-inducing. Cultural theorists such as Terry Eagleton (1983) and Harold Bloom (1973) defended the renewal of canons without treating it as a profanation of the sacred.

The idea of cultural heritage as untouchable extends far beyond the arts. Yet, in creative fields, questioning and reinterpretation are essential to keeping a work alive. A classic remains relevant when it adapts to the language of its contemporary audience without losing its core. Simon Callow (2010) reflects on the need to reinterpret canonical works to preserve their stage vitality —and on how changes in set design and costume can “resurrect” a play without altering its original text.

Group choreography. Costumes representing the most realistic side of the story.

Cabaret: Reinterpretation and Risk

The new Cabaret, now playing at the UMusic Hotel, was born from an exhaustive study of previous versions and a distinctly innovative approach to set and costume design. The central idea: a non-stage that completely redefines the relationship between audience and performers.

Sally Bowles (played by Amanda Digón) in the number Don’t Tell Mama.

How does one design a non-stage and how does that shape the costumes?

Felype de Lima, head of set and costume design, explains:

In previous versions, the club was a stage facing the audience. Then, a provocateur figure was introduced to bring the action closer. In recent American and British productions, audiences surrounded a circular stage. In our version, we’ve taken it further: we removed the stage entirely and adopted a club format, so the spectator truly feels inside the Kit Kat Klub.

A cabaret isn’t built like an Italian-style theatre. The audience is very close —they can judge the costumes from inches away, feel the sweat, and hear the voices right next to the performers. That demanded exceptional quality: fabrics, stitching, finishes.

Remedios Gómez, head of wardrobe, adds:

In theatre, we usually talk about the ‘five-meter effect’: the quality stays high, but certain tricks are allowed. Here, in Cabaret, there’s no room for that —everything has to hold up under scrutiny.

Costumes of Sally Bowles and the ensemble, featuring leather, latex, and metallic details.

Two Worlds, One Wardrobe

The costumes in Cabaret act as a bridge between two realities.

On one side lies pre-Nazi Berlin —the historical, visceral, human part of the story. Characters like Fräulein Schneider with her curlers, Herr Schultz selling pineapples and oranges, and Clifford searching for inspiration as a bohemian writer embody that humanity through their clothes.

Costumes of Fräulein Schneider and Herr Schultz, with fabrics and colors reflecting everyday realism.

On the other side, the Kit Kat Klub: a space that’s real yet flirts with utopia —freedom, desire, live performance. Here, the creative team introduced modern elements that turn materials and silhouettes into symbols of audacity, modernity, and control over one’s body.

At the Kit Kat Klub, we sought a fusion between classic and contemporary. Younger audiences today might not connect with a World War II story, but they do respond to modern visual cues. That’s why we blended historicist designs with modern materials —leather, latex, harnesses, rhinestones— adding modernity without breaking the classic essence. It’s our way of rebuilding the classic.

The Emcee and ensemble. Costumes inspired by 1930s silhouettes, updated with contemporary materials.

That ongoing dialogue between the historical and the contemporary translates into a striking visual fusion: 1930s silhouettes reinterpreted with modern materials, embellished details, and textures designed to resonate with today’s audience.

Character Evolution and Visual Narrative

In Cabaret, costume evolution isn’t merely aesthetic — it mirrors the story’s emotional journey. Characters begin in nude and skin tones, a palette that conveys vulnerability and intimacy. As the plot darkens, costumes shift to black and heavier materials, culminating in the final scenes, where the club ceases to be a refuge and becomes a metaphor for exposure, loss of light, and loss of identity.

Sally Bowles in the number Cabaret.

In that final stretch, there’s a strong visual and emotional impact reflected in both costume and set,” Felype explains. “We move toward a ‘non-place’ —a kind of prison or gas chamber, where the characters are stripped bare, not only physically but socially. And that’s visible in what they wear… or what they no longer wear.

Costume design of the Emcee during Wilkommen.

Breaking away from other readings of the musical —which have leaned toward circus-like, French, or overtly decadent aesthetics —this new production brings Cabaret closer to the present through the precision of its visual design.

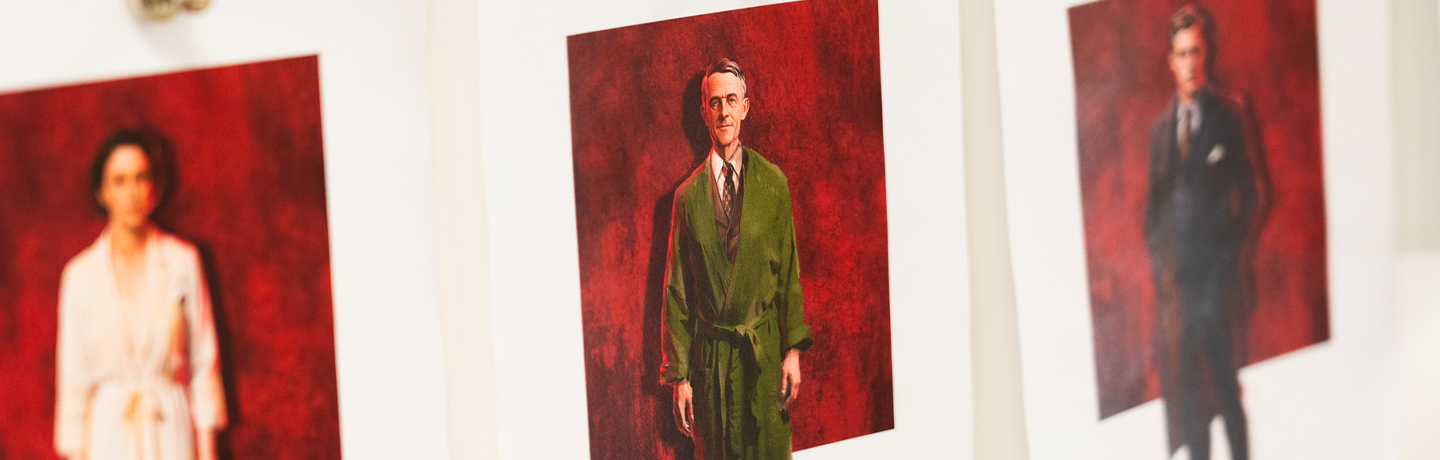

Digital design of the ensemble figurines, with color and silhouette variations according to each musical number.

The Emcee and Androgyny as Stage Language

Few characters are as aesthetically and conceptually rich as the Emcee.

Felype de Lima explains:

The Emcee is, by nature, an androgynous figure —fascinatingly ambiguous. In our version, the role is played by a woman, and we didn’t want to treat it as a male character, but rather to explore masculinity through the feminine. I’m drawn to the classic idea of the freak show —the half-man, half-woman being— and we reinterpreted it diagonally: the lower half feminine, the upper half masculine.

This duality between masculine and feminine, right and wrong, remains a question in today’s society. But it was already there then, from Coco Chanel introducing trousers for women to Marlene Dietrich, who in 1930s Berlin played with androgyny and tuxedos in film noir. It’s fascinating how that conversation remains current.

Digital figurines. The third from left is the Emcee’s hybrid tailcoat. The garment combines a masculine upper half with a feminine lower half, reflecting the gender duality of the character.

Designing the Emcee’s costumes presented both conceptual and technical challenges. One of the pieces pays homage to Marlene Dietrich — an oversized, iconic white fur coat that required extensive manual work. Other garments, like the cropped tailcoat, further emphasize the character’s gender ambiguity.

The Emcee during a scene in the Kit Kat Klub, wearing the hybrid tailcoat that blends masculine and feminine elements.

The costumes thus become a silent narrator: they accompany the story, mirror each character’s evolution, heighten dramatic tension, and let the audience experience emotion from within the club.

Universal Tensions: The Classic, the Modern, and Freedom

There is, of course, a historical frame that conditions what happens in Cabaret. Yet this LETSGO production revives tensions that remain universal.

The Emcee’s gender duality once again challenges the boundaries between masculine and feminine and invites us to question whether those oppositions are truly tensions or rather social constructions so deeply ingrained that they resist deconstruction.

Digital design of the ensemble figurines, featuring color and silhouette variations for each musical number.

In parallel, the musical sets the classic against the modern: while the narrative and script remain faithful to the original, the costumes, set design, and staging converse with contemporary references —proving that a classic can evolve without losing its identity.

It also plays with the contrast between the real and the metaphorical: the everyday Berlin of the characters versus the symbolic freedom of the Kit Kat Klub, a space where fiction mirrors society.

And finally, the tension between freedom and repression runs through the entire piece: what happens inside the club is a refuge —one that can, in the end, be taken away, reminding the audience how fragile autonomy can be under external forces.

The result is a Cabaret that speaks to its own time and to ours —a classic reborn that continues to challenge the universal human conflicts that remain unresolved.

By the LETSGO Pen, Claudia Pérez Carbonell, on October 22nd, 2025